I do not pretend to understand the complexity of geo-political relations in Afghanistan. What I do know is that Afghanistan has been at the centre of a geo-political chess board for decades, stemming back to the cold war. I know that my government is not doing enough, with its draconian stance on refugees and its willingness to leave people who helped the Australian Defence Force to their fates.

And what I know comes from a space of heart rather than logic. I have taught Afghani refugees, most of whom were from the persecuted Hazara minority. I have heard stories of lives that I couldn’t even begin to imagine. And in the comfort of my safe Australian home, I have read news reports and books written by women who fear for their future.

From the perspective of someone who has found solace in creativity, reports of the the suppression of creative life under the Taliban are chilling. Under the Taliban between 1996 and 2001, all music, art and film that did not adhere to strict religious dictates were banned. We are not just talking about so called ‘imperialist art’, the likes of which were banned during China’s cultural revolution. This was not just garden variety censorship. Historical sculptures were destroyed. Folk music and singing that existed for centuries were banned.

The Taliban is not the first regime that has attempted to suppress creative expression. Dancing was and probably still is prohibited in some Puritanical Christian sects. In Australia, we banned Indigenous music, dance and ritual in our 19th century and early 20th century missions. Historical documents show that dance and music were banned on some slave plantations in America.

There is something sinister about the banning of folk art. Most folk music is benign and ostensibly not a threat to the political structure. The trope is predictable and almost universal. There are the love stories, the hero stories, the soldier stories, the working in the field stories. This form of creativity is what unites communities, providing comfort, stability and a sense of identity. Perhaps this is why totalitarian regimes seek to destroy all creative expression, from the overtly polemic to the benign lullaby one sings with a traditional instrument.

When a person is deprived of creative thought and expression, they may become malleable and hollow. The best way to oppress a people is to kill their spirit, so they become fearful automatons. One of the things that separates human mammals from non human mammals is creative expression. In the totalitarian playbook, the creatives are always the first to be executed, along with the political dissidents. In advanced totalitarianism, all creativity is quashed.

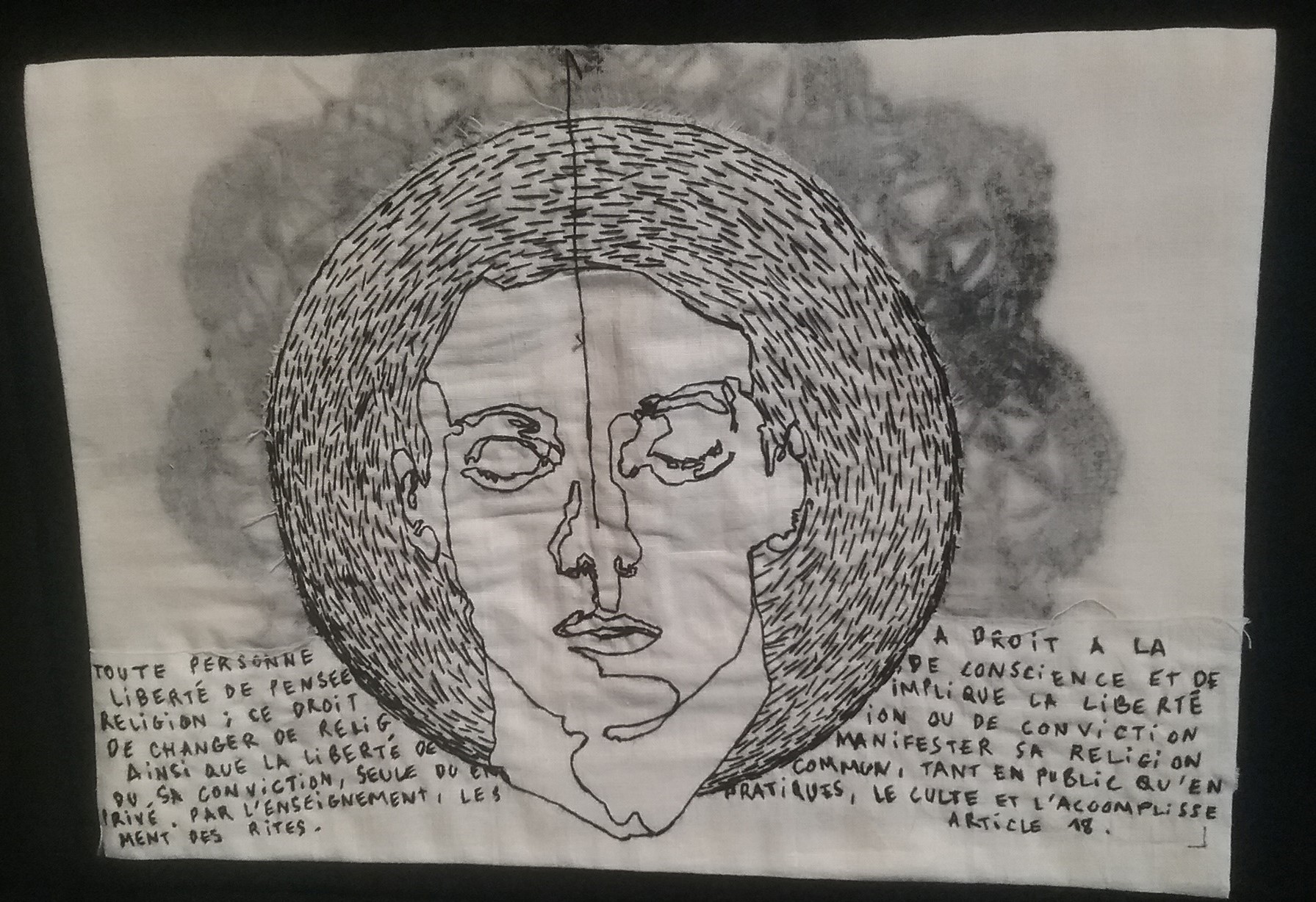

But it is not possible to oppress people forever. Humans find a way. In Pinochet’s Chile, all correspondence out of the country was intercepted, so the international community would not hear of the horrors occurring. But I have heard that women began embroidering their stories on cloth, and sending their needlepoint to their relatives overseas. In their arrogance, the regime believed that embroidery was simply something women did to pass the time, and did not stop to look at the embroidered pieces.

Closer to home, Kurdish journalist Behrouz Boochani wrote his biography ‘No Friends But The Mountains,’ on a smuggled mobile phone while indefinitely detained for seeking asylum by the Australian government.

Creative dissent cannot be completely quashed, and these examples provides a sliver of solace in the darkness.

Graffiti art from the Melbourne CBD, March 2020